« lun. 19 juin - dim. 25 juin | Page d'accueil

| lun. 03 juil. - dim. 09 juil. »

30/06/2006

In Search of His Rising Sun

By Puay-Lim SAW © 2006 Puay-Lim SAW blogSpirit

(with a modest contribution of Isabelle D. Taudière)

Puay-Lim Saw a exercé sa belle plume de journaliste dans les colonnes de la presse de Singapour, et de Hong Kong. Inlassable globe-trotter et cavalière émérite, elle partage aujourd’hui son temps entre Paris, Singapour et les ranchs de l’outback australien. C’est à Auvers-sur-Oise qu’elle a découvert Vincent van Gogh et, avec lui, un art du voyage à la lisière entre réel et imaginaire.

Gazing from the window of his train as it chugged southwards towards Arles, the artist felt his spirits rising. Yes, the landscape rolling by was looking increasingly like Japan – the Japan of his imagination, of the many woodblock prints that were all the rage in Paris then.

It was 20 February 1888 and Vincent van Gogh, almost 35, was leaving Paris for Le Midi, for its sun and a different light. Just then though, the scenery outside was snow dusted. Although surprised, he was undeterred and could still liken the country before him to the country he envisioned. In a letter to his brother Theo from Arles the next day, he wrote: ”And the landscapes in the snow, with the summits white against a sky as luminous as the snow, were just like the winter landscapes that the Japanese have painted.”

His vision endured. A month later, he was ardour epitomised in a letter to friend and fellow-painter, Emile Bernard: “This country seems to me as beautiful as Japan as far as the limpidity of the atmosphere and the gay colour effects are concerned. The water makes patches of beautiful emerald blue such as we see in crepons.” (van Gogh’s word for ukiyo-e prints).

As temperatures rose, the artist lost no time going outdoors to capture flowers, blooming orchards and the countryside on his canvas. In the land of sun-caressed hues, what looked like Japan in his eyes, became Japan in his mind. Writing to Theo that June, he reasoned: “About this staying in the South, even if it is more expensive, consider: we like Japanese painting, we have felt its influence, all the Impressionists have that in common; then why not go to Japan, that is to say, to the equivalent of Japan, the South?”

The artist even went on to urge his brother to see this for himself. “I wish you could spend some time here, you would feel it after a while, one’s sight changes, you see things with an eye more Japanese, you feel colour differently. The Japanese draw more quickly, very quickly, like a lightning flash, because their nerves are finer, their feelings simpler. I am utterly convinced that just by staying on here, I shall set my individuality free.”

If only van Gogh had been born a century later! How much less fettered his individuality might have been. And his passion for art, coupled with his constant yen to better himself, to experiment, and to explore new horizons, would surely have taken him east – to the land of the rising sun – Japan itself.

Imagine for a moment now that he was born again on 30 March 1953. Given another time, another pace, how might have his life as an artist unfolded?

It’s early morning one day in late March 1988. Through the window of his plane as it approaches Tokyo, our modern-day Vincent gazes enraptured at the wondrous landscape below, effused in the soft pink tints of its spring blossoms.

The artist can hardly contain his excitement. Straight after checking into a modest inn in the heart of the city, he sets out in search of Tokyo’s best gardens. His brushes see little rest in the next few weeks as he lingers in Ueno Koen, Shinjuku Gyoen, Yogogi Koen, Rikugien and the Imperial Palace of East Gardens, delighting in the riot of colours unleashed by the countless flowers that have burst into bloom. Soon he has completed dozens of tableaux featuring sakuras (cherry blossoms), botans (peonies), ayames (irises) as well as Japanese varieties of azaleas, daffodils, daisies, pansies, petunias, tulips…

Meanwhile, he has found no shortage of other subjects for his palette in Tokyo, with its mix of modernity and tradition. A keen observer of humanity and society, he relentlessly explores the quartiers populaires reminiscent of yesteryear’s “floating world”, his keen eye capturing vivid life and street scenes through numerous renderings of children, housewives, peddlers… Not one to abhor the districts of pleasure, he has already befriended a few courtesans and their portraits soon grace a couple of canvasses. He has also struck up an acquaintance with a group of sumo wrestlers whose physique and lifestyle make them intriguing models.

For all its allure, the bustling city life soon exhausts him, the way the frenetic energy of Paris wore van Gogh out in 1888 after nearly two years, as he explained in his first letter to Theo from Arles: “It seems to me almost impossible to work in Paris unless one has some place of retreat where one can recuperate and get one’s tranquility and poise back. Without that, one would get hopelessly stultified.”

Not surprisingly then, after an interval in Tokyo, the artist in 1988 finds himself escaping from the metropolis and its millions of people scurrying about amidst a clutter of skyscrapers and a dazzling kaleidoscope of neon lights and billboard signs.

Happiest when outdoors either painting or taking long hikes, he explores the Japanese countryside, communing with nature and regaining his focus on what he sees as essentials. With his empathy for those who toil with their hands, he sets up his easel frequently to paint farmers, their cottages and land. Awed too by the beauty of Japan’s multitude of islands, he renders with his palette a spectrum of seascapes, some saluting fishermen at work; some, fishing vessels; others, only the sea, sky and coastlines in all their lonely majesty.

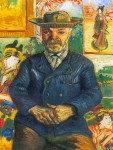

His excursions also take him to Kyoto for its temples and shrines, Fukuoka for its hot springs, and the mystical Mount Fuji, which back in Paris in the autumn of 1887, his earlier self had juxtaposed lurking playfully above the hat of of Père Tanguy, in two portraits of his Parisian paint supplier.

Back in the mid 1880s van Gogh’s discovery of Japanese art was to influence his metamorphosis as an artist considerably. At the time, Japan had begun opening its ports to the outside world after centuries of physical and cultural isolation. This development triggered an enthusiasm from the West for everything Japanese. In Paris, collectors and Impressionists painters were snapping up readily available woodblock prints, acutely sensitive to their sophisticated subtlety and increasingly aware of the most refined examples of this art form.

Although van Gogh had seen and bought his first Japanese woodblock prints with their bright colours and expressive character in the Netherlands in 1885, it was only in Paris that he and Theo collected these in a big way, acquiring them mainly from the modest shop of Père Tanguy and the classier gallery of Siegfried Bing in Montmartre.

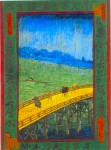

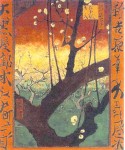

Initially, his appreciation of Japan was mostly pictorial and provided a technical benchmark he yearned to achieve. Fascinated with the aesthetics of both the art and the calligraphy, he emulated his models through three pieces of japonaiseries copied from leading ukiyo-e masters. Although he injected some humorous cross-references to the world of prostitution in his interpretation of Keisai Eisen’s Oiran (or Courtesan), he probably did not intend the irony in the Japanese characters picked randomly to frame his versions of Utagawa Hiroshige’s Flowering Plum Tree and Bridge in the Rain — a prosaic advertising for a maison de plaisirs for the latter painting!

After moving to the South, the artist strove to reach beyond this academic vision of Japanese art and embrace its underlying spirit, as he explained to Theo: ”I envy the Japanese the extreme clarity of everything in their work. It is never dull and it never seems to be done in too much of a hurry. Their work is as simple as breathing, and they do a figure in a few sure strokes as if it were as easy as doing up your waistcoat.”

His renewed closeness to nature in Le Midi soon gave him great spontaneity and led him to appropriate fully the Japanese mind, and indeed, to re-create his own imaginary Japan through a very personal interpretation of his actual environment: “Come now, isn’t what we are taught by these simple Japanese, who live in nature as though they themselves were flowers, almost a true religion? And one cannot study Japanese art, it seems to me, without becoming much merrier and happier, and we should turn back to nature in spite of our education and our work in a world of convention,” he told Theo.

Imbued with this philosophy, his pursuit of a whimsical Japan took him outdoors as much as he could and he created a treasure trove of tableaux celebrating sun-soaked landscapes, open fields of flowers and orchards in full bloom.

Interestingly, van Gogh’s depiction of flowers during his short career as an artist from 1881 to 1890, traces both the evolution of his genius and his romance with Japan, which, in effect, mirrors his search for the perfect setting to realise his full potential as a painter and a human being.

During his early years as a struggling artist in Holland, van Gogh hardly ever picked flowers as his subject. And when he did, he limited himself to still life cast in drab tones of mainly brown and grey. After moving to Paris in March 1886, under the dual influence of the Impressionists and Japanese woodblock prints, he started to view flowers with a different eye and his palette brightened up considerably. At the same time, he began infusing his subjects with more energy and life, reflecting his own increasing optimism.

“Last year I painted almost nothing but flowers so as to get used to using colours other than grey, vis. pink, soft or bright green, light blue, violet, yellow, orange, glorious red,” he wrote to his sister Wilhelmina in the autumn of 1887 from his Montmartre studio.

By the time he settled down to life in Le Midi, van Gogh had basically found his Japan, as evidenced in so many of his works of the early Arles-period, such as Pink Peach Tree in Blossom, and Blossoming Pear Tree.

Soon, he had internalised his ideal Japan to the point where he no longer needed to rely on the original models: He had now turned Japan into a perfect Utopia that lived in him. “For my part,” he explained to Wilhelmina in September 1888, “I don’t need Japanese pictures here, for I am always telling myself I am in Japan. Which means that I have only to open my eyes and paint what is right in front of me if I think it effective.”

From then on, wherever he was, he would mentally be in Japan. His beautiful Blossoming Almond Tree, painted in Saint-Rémy in February 1890, may be the most eloquent illustration of this state of mind. Although he was often confined indoors in an asylum during this period, the Japan within him shone through clearly in this work.

In this sense, Japan was, in fact, never a destination in itself, only a long stop-over in his journey for answers and ideas, and a means to “set his individuality free”. As he reminded Theo in a letter from St Rémy in September 1889, ”I came to the south and threw myself into work for a thousand reasons. Wanting to see a different light, believing that observing under a brighter sky might give one a more accurate idea of the way the Japanese feel and draw…”

This achieved, he longed for the North again, which he now wanted to reconsider with his “Japanese eye”: “Now that most of the leaves have fallen, the countryside is more like the North, and then I realise that if I returned to the North I should see it more clearly than before.”

But van Gogh also understood that this quest for a vision would take him on an endless voyage: “I always feel I am a traveller, going somewhere and to some destination. If I tell myself that the somewhere and the destination do not exist, that seems very reasonable and likely enough,” he had confided to Theo back in 1888.

Similarly, our 20th century Vincent will yearn to move again and return to the West after seeing Japan and fulfilling many dreams in the East. Making the best of flight options, he seizes every opportunity to keep going somewhere and to some destination that exist physically, in that quest to improve his style, and for other answers his mind and soul seek. Between flights, the frequent-flyer-artist cannot miss the quaint old village of Auvers-sur-Oise, where his earlier-self spent the last two months of his life, and which has been an artists colony since the mid 1800s, attracting painters such as Paul Cézanne, Camille Pissarro, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Charles-Francois Daubigny and Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot. Seated at the painters’ table at Auberge Ravoux, he shares his experiences and many home-styled meals with kindred spirits.

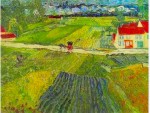

One feature that would most certainly strike the modern-day Vincent there is the remarkably unchanged landscapes around Auvers that had stimulated van Gogh so strongly in 1890 and inspired the celebrated Landscape with Carriage and Train in the Background, of which he explained to Wilhelmina: “I am working a good deal and quickly these days; by doing this I seek to find an expression for the desperately swift passing away of things in modern life.”

Should the contemporary Vincent paint his own version of this tableau a hundred years later, he would do it much the same way, but cruising above a now steamless train, would be a jet observing the departure of the carriage from the scene. Admirers of Vincent van Gogh can see Dr. Paul Gachet’s collection of the artist’s works at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris.

Admirers of Vincent van Gogh can see Dr. Paul Gachet’s collection of the artist’s works at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris.

At Auvers-sur-Oise, some 35 kilometres north of Paris, they will find the artists village intact and Auberge Ravoux, which houses van Gogh’s last room as well as the painters’ table he so often sat at during his stay there.

The Musée Van Gogh in Amsterdam has the largest collection of van Gogh’s paintings and the two brothers’ collection of Japanese woodblock prints.

In Japan, most of van Gogh’s paintings belong to private collectors, but the following have one or two works each: the National Museum of Western Art, the Sompo Japan Museum of Art and the Bridgestone Museum of Art (two pieces) all in Tokyo; and Osaka’s Takahata Art Gallery.

23:40 Publié dans Vincent Van Gogh | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | | |  |

|  Digg

Digg